Photo Credit: Andrew Allard ’25

Andrew Allard ’25

Executive Editor

Could recent controversial constitutional law decisions bring about renewed interest in direct democracy? Through his research, Professor Xiao Wang has found that not only is a new wave of grassroots democracy already here, but also that this response finds precedent in U.S. history.

Last Monday, in celebration of Constitution Day, Professor Wang returned to his alma mater, the Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy at the University of Virginia, to present his research to a packed room of students and faculty. Professor Wang, an Ohioan, opened with a recent example from his home state, where a referendum to be held on November 7 will decide whether to enshrine reproductive rights, including abortion, in the Ohio Constitution.[1] In August, a second proposed amendment supported by the Republican Party of Ohio would have made it more difficult to amend the state constitution by increasing the referendum threshold from a simple majority to 60 percent.[2] That proposal was rejected by voters.[3]

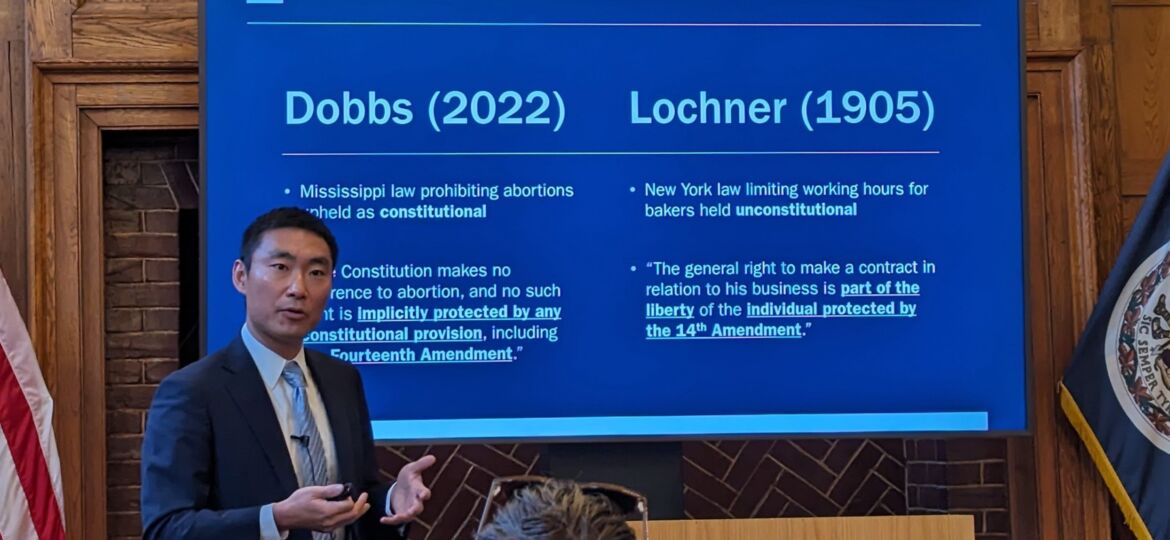

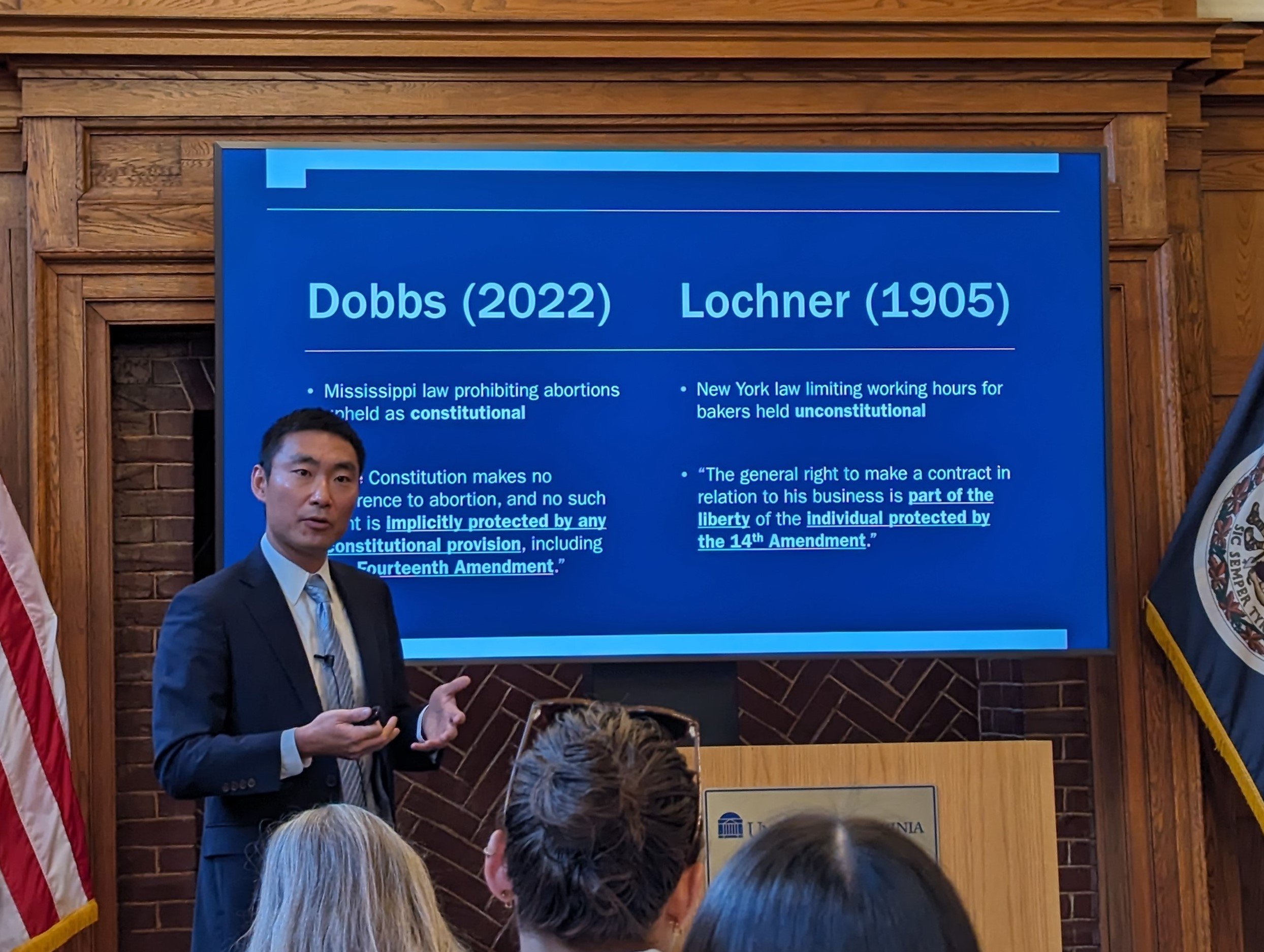

Voters today, Professor Wang explained, are using the referendum process to protect abortion rights in response to the Dobbs[4] decision in 2022. Both the decision itself and Ohio officials’ efforts to entrench the status quo garnered backlash from the public, with one commentator noting, “[O]ur courts have been stacked, our lawmakers have been captured by special interests, our politicians are riddled with corruption, and now our own majority voter power over our constitution is being assaulted.”[5]

In this country that so reveres its Constitution and the rule of law, such a strong rebuke of the legal system is rare. But, as Professor Wang points out, it is not without precedent. Professor Wang’s research suggests that Ohio’s constitutional referendum process grew out of popular dissatisfaction with the courts. As Professor Wang explained, at the turn of the 20th century, the Supreme Court produced some of its most controversial opinions, including Plessy v. Ferguson[6] and Lochner v. New York.[7] In 1912, seven years after Lochner, Ohio held a constitutional convention, during which it adopted its modern referendum process. Proponents of the new referendum process explicitly criticized the courts and judicial review. As one representative put it, “No such power was ever given to the courts. They have simply taken it.”[8]

Ohioans were not alone. Of the twenty-six states that today have ballot initiative or referendum processes in their constitutions, twenty-one enacted them between 1898 and 1918, Professor Wang explained. “You see this sort of popular resentment of the Supreme Court—this idea that these people might interpret the law, but we don’t have to adhere to every one of their court cases. We can have a voice in this.”

But in spite of the tradition of popular constitutionalism in some states, challenges to direct democracy have proliferated in recent years. For example, Amendment 4 in Florida—adopted by 65 percent of voters[9]—sought to end felony disenfranchisement “upon completion of all terms of sentence.”[10] Within less than a year, the Florida Legislature adopted a new law that continued to withhold the right to vote from felons until they paid all outstanding legal financial obligations, without providing a reliable means of determining these obligations—effectively limiting the scope of Amendment 4.[11] Even more astoundingly, in Mississippi, after 73 percent of voters approved an initiative legalizing medical marijuana, the Mississippi Supreme Court struck down Mississippians’ constitutional right to vote in ballot initiatives altogether.[12]

Professor Wang believes that these efforts to stymie popular initiatives have undermined the public’s confidence in government. “It totally makes sense why most people are disillusioned and disengaged.” But Professor Wang, undeterred, suggested that direct democracy can supplement the courts’ role in constitutional interpretation. “The way that we understand [the Constitution’s] relationship to us, what we owe it and what it owes us, how we read it—that constantly changes.”

Noting that defining the Constitution is an ongoing conversation, Professor Wang suggested that legislative change, judicial reform, and direct democracy can all contribute. In closing, Professor Wang implored students to remain involved in that conversation. “Please, for the time that you’re here and the time that you’re out of here, never forget that part of you that wants to see policy change. Use it to make a difference.”

—

tya2us@virginia.edu

[1] Julie C. Smyth & Samantha Hendrickson, Voters in Ohio reject GOP-backed proposal that would have made it tougher to protect abortion rights, AP News, https://apnews.com/article/ohio-abortion-rights-constitutional-amendment-special-election-227cde039f8d51723612878525164f1a (Aug. 9, 2023, 9:26 AM).

[2] Id.

[3] Id.

[4] Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Org., 142 S. Ct. 2228, 213 L. Ed. 2d 545 (2022) (finding that there is no constitutional right to an abortion).

[5] David Dewitt, Ohio government is already captured by radical special interests. State Issue 1 would make it worse, Ohio Capital Journal, https://ohiocapitaljournal.com/2023/06/29/ohio-government-is-already-captured-by-radical-special-interests-state-issue-1-would-make-it-worse/ (June 29, 2023, 4:30 AM).

[6] 163 U.S. 537 (1896) (creating what became known as the “separate but equal” doctrine).

[7] 198 U.S. 45 (1905) (striking down a New York statute restricting working hours for bakers on the basis of a Fourteenth Amendment freedom to contract).

[8] C. B. Galbreath & Clarence E. Walker, Fifty-second Day, in Proceedings and Debates of the Constitutional Convention of the State of Ohio 1087, 1091 (E. S. Nichols, ed. 1912).

[9] Brennan Ctr. for Just., Voting Rights Restoration Efforts in Florida (Aug. 7, 2023), https://www.brennancenter.org/our-work/research-reports/voting-rights-restoration-efforts-florida.

[10] Fla. Const. art. VI, § 4.

[11] Brennan Ctr., supra note 8.

[12] The Mississippi ballot initiative procedure, adopted in 1890, limited the total number of signatures that could be counted from each of the state’s five Congressional districts to one-fifth of the total number of required signatures. After the 2000 Census, Mississippi lost a congressional seat, leaving it with only four. The Mississippi Supreme Court held that this rendered the state constitution’s ballot initiative procedure inoperable. See Initiative Measure No. 65: Mayor Butler v. Watson, 338 So. 3d 599, 607-08 (Miss. 2021).