This article appears in the October 2023 issue of The American Prospect magazine. Subscribe here.

It was hard to say who won the war of words at the St. Jerome Fancy Farm Picnic in western Kentucky, the summer festival of food, fun, and games that bills itself as “the world’s largest one-day barbecue.” What the 143-year-old Catholic church fair really does is kick off Kentucky’s campaign season with a rowdy, old-school beatdown starring candidates for public office.

Andy Beshear, the Democratic governor now seeking re-election, led the pack with all the positivity that an incumbent could radiate. He labeled the election “a contest over vision and di-vision.” Shouting over chants of “liar, liar, liar” from opponents in the crowd, Beshear pointed out how people responded to the severe storms that hit the area in July and underlined his administration’s three years of job creation, the billions of dollars of investment in the region, and the hundreds of bipartisan bills he worked to pass.

Daniel Cameron, the Republican attorney general trying to replace him, wound up his fans with one-liners on Bud Light’s marketing and new pronouns for the governor (“has and been”), and threw out GOP buzzwords like “law and order.” The Republican’s camp dutifully booed his Joe Biden mentions on cue.

A good time was had by all. Abortion never came up.

More from Gabrielle Gurley

This uneasy silence on one of the most divisive topics in American politics ended during Labor Day weekend, however, when Beshear dropped a 35-second ad that put abortion front and center. “Daniel Cameron thinks a nine-year-old rape survivor should be forced to give birth,” intones Erin White, a Jefferson County prosecutor. Sidestepping both the critique and immense harms that victims suffer, Cameron had a surprisingly weak response to Beshear’s salvo. He touted his “pro-life” stance and criticized the governor’s “desperate attack.” Three weeks later, Cameron retreated from his repeated stance on a total ban and said that he would support rape and incest exceptions.

Abortion isn’t the only issue shaping this November’s statewide elections in Kentucky. It certainly isn’t in Mayfield, a city of 10,000 people still recovering from a devastating tornado nearly two years ago and this summer’s torrential rains and massive flooding. Crystal Fox, the president of the Mayfield Minority Enrichment Center, had praise for the governor. “Since the tornado, he’s been on the ground a lot,” she told the Prospect. “By contrast,” she claims, Cameron “hasn’t really been seen in the area as much.”

But she had questions about how donated tornado relief funds were used and thought that the money could have been “better spent.” Moreover, plenty of residents including Fox herself also got tangled up in the red tape that slows down FEMA aid to victims of natural disasters in a place where nearly one-third of people live in poverty. “Before the tornado, people didn’t have their basic needs met,” she says. “So, after this tornado, it just amplified those issues.” In Mayfield, Fox says, the community’s attention is in the “long process” of recovery.

Last year, when Kentucky voters rejected a proposed constitutional amendment that would have eliminated any constitutional right to an abortion, the vote in Graves County, where Mayfield is the county seat, was lopsidedly in favor of the measure. By a 69 percent to 31 percent margin, county voters backed the amendment, which said that the state constitution did not “secure or protect a right to abortion” or funding for abortion. Statewide, the amendment was defeated by a five-percentage-point margin.

In Mayfield today, Fox says, “I don’t think it [abortion] is one of the issues that we’re seriously focused on.” She recognizes that this year, the candidates “are also trying to get everybody backing them from all over the U.S., with speaking about gender issues and abortion issues and things like that, and not just focusing on issues that play just to Kentuckians.”

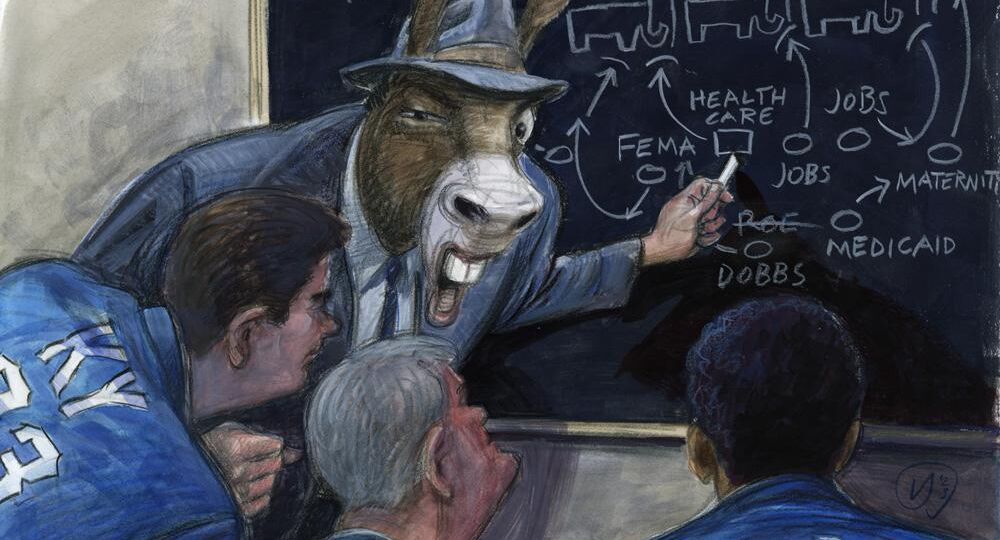

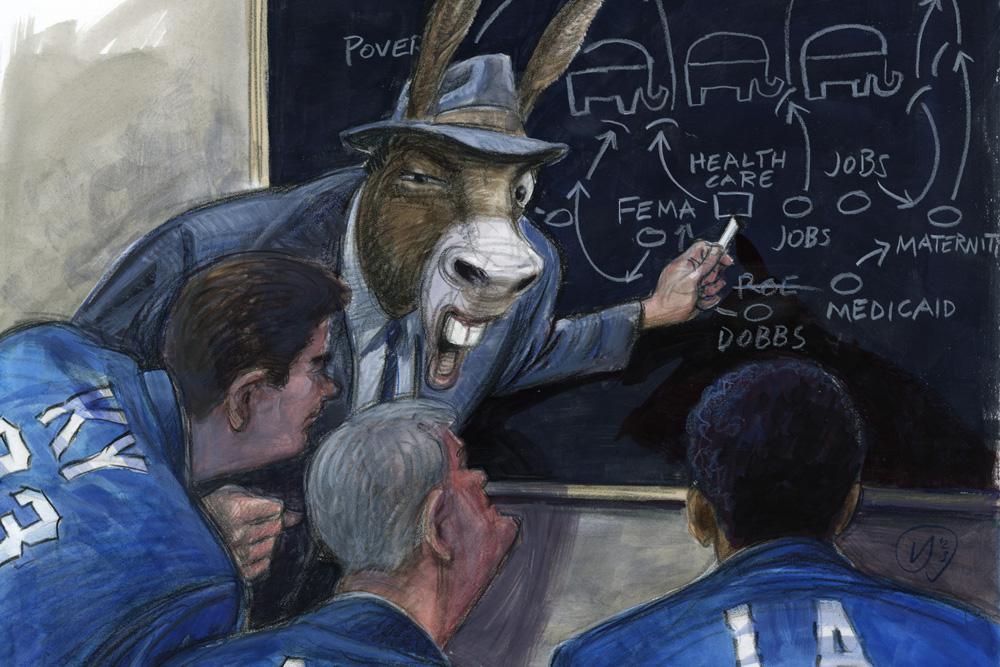

The question is whether such a gambit will work for Beshear. It is a gutsy, risky departure from how Democrats in the state usually win by keeping to Kentucky-centric problems and staying out of national war zones. But the amendment’s defeat signaled that many Kentucky voters are uncomfortable with what Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization means.

And not just in Kentucky. Since Dobbs, voters in Republican Kansas, Ohio, and Montana have rejected far-right overreaching ballot measures and affirmed their support for the right to abortion even with curbs in place. In last year’s midterm elections, voters’ concerns about the loss of that right helped keep the Senate in Democratic hands and blunt the Republican wave in the House that overconfident prognosticators repeatedly claimed was nigh.

This fall, upcoming gubernatorial elections in Kentucky, Mississippi, and Louisiana will test just how deep the revulsion over these far-right Republican excesses runs in the South, and what those races may presage in abortion access politics beyond the region. All three states have Republican supermajorities in their legislatures. The Dobbs decision specifically affirmed a Mississippi statute devised to explicitly challenge Roe v. Wade. But many Republicans have been shaken by the backlash.

Beshear heads into November with a page taken straight from the Democrats’ 2022 midterms playbook. In Mississippi, Republican Gov. Tate Reeves took up the abortion issue in broad strokes at the Neshoba County Fair to hit back at his Democratic challenger, Brandon Presley, a Mississippi Public Service Commissioner who oversees utilities issues in the state’s northern district. The governor was all but obliged to bring up the issue to deflect attention from his main electoral liability: being tangled up in a huge welfare scandal. Presley, who avoided the abortion issue altogether at Neshoba, prefers simple pro-life declarations while sticking to a Magnolia State script slamming the governor on corruption and the state’s health care crisis. Whatever exists of a pro-choice constituency in Mississippi, Presley isn’t playing to it, though he clearly hopes to win those voters and others who are sick of scandals and the state’s persistent health care crisis.

Louisiana holds its open primary in mid-October. Gov. John Bel Edwards, an anti-abortion Democrat, is term-limited. Republican Attorney General Jeff Landry, who is running to succeed Edwards, sticks to the loud and proud extremes favored by the far-right Republicans on abortion. If he survives attacks from his Republican opponents in the already nasty “jungle” primary, he appears to be poised to romp over Democrat Shawn Wilson, an African American former state transportation secretary and first-time candidate with pro-choice proclivities and little statewide name recognition. Like their Mississippi neighbors, Louisianans mostly vote along racial lines.

The symptoms of Republican overreach have produced three different responses from the gubernatorial candidates in these states. Beshear hopes to beat back Republicans’ culture-war theatrics, and get women, people of color, young people, and disgruntled Republicans—particularly those conservative women who oppose extreme abortion restrictions—to vote for him in the numbers he needs. Presley hopes that a pathway through homegrown crises can give him a chance. And Louisiana may indicate whether there’s a downside for a future governor in a Deep South state who promises even more extreme abortion restrictions.

Will cracks appear in the Republicans’ hold on the South due, in part, to abortion, and will they spread as the post-Dobbs real-world turmoil inflicted on pregnant people comes into full view?

KENTUCKY ABORTION SUPPORTERS AND OPPONENTS have been involved in near-constant litigation with a steady stream of limitations implemented in the years between Roe v. Wade and Dobbs. The state passed 17 abortion-related bills between 2010 and 2019 that restricted everything from public funding of abortions to licensing of clinics and dispensing of educational information, while instituting bans on telemedicine abortions and on certified midwives’ right to perform the procedure.

The 2019 trigger law, which came into effect after the Court revoked Roe, prohibits abortion except in cases when the person’s life is in danger or a medical procedure accidentally results in termination of the pregnancy. There are no exceptions for rape or incest. There is also a six-week ban on the books. That supersedes any other law, so even if the trigger ban were overturned, abortion would still be banned at six weeks.

The current situation is one of the most extreme in the country. With few medical professionals confident that they understand the statute’s real-world implications in clinical settings, a woman needing an abortion will most likely have to head out of state for the procedure.

Louisville had two abortion clinics before the Dobbs ruling; people from opposite ends of the state had to drive five or six hours to get to them. “Now people have to cobble together money to do GoFundMe’s, ask you to send money to their cash app in order for them to travel outside of the state to access abortion care,” says Attica Scott, a former Democratic state representative for a Louisville district. She worries that closing clinics also compromises other reproductive health services that these facilities offered, including gynecological examinations.

Fears are growing that birth control, too, may be targeted in the 2024 legislative session that begins in January. “There certainly were murmurings after the ballot win that we had in 2022,” says Scott. “But I will say, even during my time in the state House, there will almost always be some legislator who would say, ‘Hmm, we need to start looking at birth control,’ and whether or not that’s a form of abortion, which was a really ridiculous conversation.”

Republicans who take a no-exceptions stance supporting the state’s current law, which still bans abortion in cases of rape and incest, have handed Beshear an advantage. Strong majorities of Americans support the right to an abortion in pregnancies resulting from rape and incest. Raising the issue of exceptions is likely to help Beshear turn out the vote in the state’s liberal and prosperous “Golden Triangle” of Louisville, Lexington, and the northern Kentucky suburbs of Cincinnati where opposition to last year’s constitutional amendment was strong, as well as in a number of Republican counties where opposition from women more narrowly tipped the amendment into defeat.

Before the Supreme Court reignited the controversy, Beshear had been keeping a relatively low profile on abortion. (“Roe v. Wade had it generally right,” he has said.) The gap that’s now opened between Beshear and the Republicans in the post-Roe environment “helps mobilize pro-choice voters who now feel that they need to fight in a way they didn’t while operating under the umbrella of Roe v. Wade,” says D. Stephen Voss, a University of Kentucky political science professor. “But leaning into the abortion issue also helps with those swing voters who are neither pro-choice nor aggressively anti-abortion, who form sort of the muddy middle on the issue.”

“We talk about abortion as if there are two sides: pro-choice people and anti-abortion people,” he adds. “But the vast majority of people [in Kentucky] did not support the permissiveness of the Roe v. Wade regime but still support abortion rights to some level.”

“Kentucky laws are no longer anywhere near the muddy middle, they’re very restrictive,” Voss continues. “Those nonideological swing voters now lean leftward compared to the status quo.”

Beshear ranks among the country’s most popular state chief executives, drawing some support even from Republicans.

This landscape helps Beshear go after the GOP’s extremism while leaving plenty of room for other issues. So far, some of the added sizzle in his campaign has come from his not revealing how he might respond if Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell’s health issues force him to step down. The Republican legislature passed a law requiring Beshear to select an interim successor from a list drawn up by McConnell’s fellow Republicans. Beshear has argued that since an “unelected and unaccountable” state GOP executive committee would compile this list, it violates the Constitution’s 17th Amendment, which pried the selection of senators away from state lawmakers and gave it to voters. Beshear may or may not contest—he is not commenting— that state law in court should McConnell resign.

Beshear is the popular son of a popular governor; his father served two terms beginning in the late aughts, and the son now ranks among the country’s most popular state chief executives, drawing some support even from Republicans. He’s been sure-footed particularly on education and closing the digital divide. His 2022-2024 budget included an 11 percent pay increase for teachers, forgiving teacher loans, and establishing universal pre-kindergarten. Broadband expansion to under- and unserved rural communities has been a constant focus, too.

Former President Trump endorsed Cameron, a McConnell protégé, early on. So far, Cameron has been able to navigate the lines between the Trump and McConnell factions. Drawing on this year’s culture-war themes, he’s hit Beshear hard and often on transgender athletes in schools and his veto of a bill, overridden and now law, that places strict bans on reassignment surgery for minors and blocks other gender-affirming care.

Following the venerable Republican playbook, Cameron, who is African American, has also gone all in on law and order, proposing $5,000 in recruitment and retention bonuses for officers, the death penalty for police homicides, and denying subpoena power to civilian review boards. Embracing the GOP’s war on cities, he has singled out Louisville, the state’s largest city, for its surging crime rates. Conversely, he has been blasted, particularly by Black activists in Louisville, for failing to secure state charges against three of the four police officers involved in the death of Breonna Taylor. Taylor’s mother is actively campaigning against him.

Cameron has only cautiously weighed in on abortion. Before the May GOP primary, he said that he opposed a bill that would have allowed a woman who has an abortion to be charged with murder. In June, along with 18 other Republican attorneys general, he objected to a federal plan to “support reproductive health care privacy.” That rule would curtail the ability of state officials to access medical records of people who go out of state to get an abortion. When asked if the state planned to prosecute people who go out of state for care, Cameron replied that Kentucky would not “prosecute pregnant mothers.”

WHILE VOTERS IN KENTUCKY HAVE AFFIRMED at least some level of support for abortion rights, most statewide political candidates in the Deep South, regardless of party affiliation, have long expressed strong anti-abortion stances if they wanted to get anywhere near a win.

Southern Democrats began their exodus to the Republican Party after Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act—a development Johnson anticipated. In Mississippi, the parties split along racial lines, with Blacks voting Democratic and whites, Republican. Mississippi is 38 percent African American, the highest percentage in the United States. That means a white Democrat like Brandon Presley not only has to turn out the Black vote but has to attract white moderates, independents, and even some Republicans, who may not like Tate Reeves but may also resist crossing over to vote for the “Black party.” Presley’s pro-life stance is one way for him to convey to conservative whites, especially men, that he shares their values.

In Louisiana, where 33 percent of the population is Black, a conservative Democrat like John Bel Edwards, the outgoing governor, took strong stances on an issue like abortion that resonated with white Republican voters.

Owing to its Mountain South heritage, Kentucky has a stronger tradition of two-party competition than the Deep South states. During the Civil War, the state never joined the Confederacy and tens of thousands of Kentuckians fought either for the North or the South. Later, Jim Crow Democrats became as entrenched here as they did elsewhere in the South. Many Black Kentuckians joined the Great Migration, and today, unlike Mississippi and Louisiana, Kentucky is predominantly white, with African Americans making up only 9 percent of the state’s population.

Democrats dominated state politics for most of the 20th century. Conservative Republicanism made inroads only beginning in the 2000s, and the numbers of registered Republican voters only surpassed Democratic voters for the first time last year. In certain regions, like the southeastern corner of the state, social conservatism melds with an economic populism that translates into Republican votes for Beshear.

In the South, abortion has a distinct racial component that rests on the othering of Black women. An unmarried woman having a child is a stereotype associated in many of parts of the South with African American women. Some religious African Americans, like some of their white counterparts, support abortion access but also want certain restrictions, such as a specified number of weeks.

The fight over the Equal Rights Amendment in the 1970s helped conservative Republicans split off some white women from the moderate wing of the Democratic Party, especially deeply religious Southern women with traditional ideas about women’s lives. The anti-ERA movement led by Phyllis Schlafly, a conservative Catholic lawyer, joined forces with the Southern Baptist Convention, the largest Protestant denomination in the United States, to stigmatize abortion. Until the ’70s, the group had supported abortion in cases of rape or fetal abnormalities or for the mother’s mental or physical health. Linking abortion with feminism played a role in moving the region to an aggressively anti-choice position.

“Abortion really gets this shame label in a deliberate effort to galvanize religious white women to vote against the Equal Rights Amendment,” says Angie Maxwell, director of the Blair Center of Southern Politics and Society at the University of Arkansas. She explains abortion politics in the South as being more about identity than politics, which translates into pro-life women thinking, “I am a good person; I am a good woman; I meet standards of womanhood; I want to be a mom at some point; I care about children.” Abortion, she says “gets put into a category of a sinful, bad, shaming kind of woman.”

With the advent of Ronald Reagan, “the moderate Republican Party nationwide remade itself in this conservative, Southern white image, this Deep South image,” says Maxwell. “In a sense,” she adds, “Kentucky seems very Southern in its fight, when that was nationalized, even though historically it’s got a lot more two-party competition than a place like Mississippi or Louisiana.”

MISSISSIPPI PASSED AN EXPLICIT ABORTION PROHIBITION in the 1950s and added an exception for rape in the mid-1960s. In 2007, state lawmakers passed a ban that would be triggered if the Supreme Court ever revoked Roe. In 2011, however, Mississippi voters weighed in on an amendment to the state constitution that read: “Should the term ‘person’ be defined to include every human being from the moment of fertilization, cloning, or the equivalent thereof?” They ended up crushing the amendment, 58 percent to 42 percent, shocking political observers who thought that they had the South all figured out on abortion.

What those observers had failed to take into account was how defining personhood came to be seen as governmental overreach, not only in urban areas like Jackson but especially in rural Black regions. Nor could anti-abortion advocates fully answer questions about how far these amendments would go after medical professionals warned of a cascade of problems stemming from decisions that would grant fertilized eggs in in vitro treatments the status of persons and potentially could outlaw contraceptives.

Chris Kromm, executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies, a nonprofit research and media center, says Southern attitudes are not as “calcified” as the rest of the country thinks. “Part of the messaging that effective Southern candidates have done is to really paint this as extreme overreaching into people’s lives that limits the choices they can make and takes away health care from them,” he says. “When you frame it in that way, there’s definitely a lot more support.”

However, Mississippi’s conservative Republican establishment struck back in 2020. After voters passed a medical marijuana ballot initiative, the state supreme court, one of the most conservative in the country, found the state’s initiative framework unconstitutional on a technicality. (An outdated constitutional provision refers to obtaining signatures from five congressional districts; the state has only four.) Although the legislature went on to pass medical marijuana legislation, the court ruling also ended up invalidating the entire ballot initiative framework, since the legislature had failed multiple times to change the language. The court’s decision also invalidated a Medicaid expansion ballot initiative that the secretary of state had certified. It also prevented future initiatives on abortion. State lawmakers’ failure to come up with a fix appears to be motivated by the fear that any vote involving abortion in Mississippi might go the way of Kansas, Ohio, and Kentucky.

Today, Mississippi law bans abortion except in cases where the life of the mother is threatened, and in cases of rape as long as there has been an official complaint to law enforcement. Such complaints are rare. Over a three-year period from 2019 to 2021, only 20 rapes were prosecuted in Mississippi.

To the degree that abortion is up for discussion this year in Mississippi, the debate isn’t between the two men running for governor; it’s between the women in the attorney general’s race: Democrat Greta Kemp Martin, a disability rights attorney, and the incumbent Republican attorney general, Lynn Fitch, the architect of Dobbs who argued the case before the Supreme Court. But though she’s way out in front in the polls, even a true believer like Fitch doesn’t want to rile things up. She stayed away from the topic at the Neshoba County Fair, a premier platform for statewide candidates—save for a quick concluding mention of “crossing into the new Dobbs era” (“exciting,” she called it) that requires fixes with everything that’s wrong with family policies from child care to the state’s “broken” adoption and foster care systems. In 2022 at the fair, she stepped right up to the mic to take a victory lap on Dobbs.

THE PINK HOUSE, THE STATE’S LONE ABORTION CLINIC for 23 years, operated by Jackson Women’s Health Organization, is now a luxury furniture and home decor consignment shop. The clinic closed the day before the state’s trigger ban took effect after the Dobbs decision. Jamie Bardwell, co-founder and co-director of Converge, which provides family planning care, describes the general reaction of Mississippians to the ban as “Wait, I thought abortion was already illegal.” It was, she says, “like the bomb that didn’t drop.”

The irony of the Mississippi gubernatorial race is that even though health care has emerged as a top issue, reproductive issues have received little attention. Mississippi is so far out in front in so many grim health metrics that it could be in a category by itself. In a country with worsening maternal health outcomes, Mississippi has continuously and conspicuously failed its women. Its infant mortality rate is the worst in the country at 9.39 deaths for every 1,000 babies in 2021, a five-year high. Black women had a maternal mortality rate four times higher than white women. There is no neonatal intensive care unit in the mostly Black and rural Mississippi Delta. A person has to go to Jackson or Memphis for a maternal fetal specialist.

Contraceptive access isn’t any better. “A lot of providers, for example, would counsel especially Black women or young people to choose certain methods based off of what they thought was better for their bodies,” says Jitoria Hunter, Converge’s vice president of external affairs. “They didn’t have access to the wide range of FDA-approved options for contraception.”

Poor reproductive health joins a long list of health care burdens that contribute to Mississippians’ abysmal health profiles. What gives Medicaid expansion supporter Presley some leverage with conservative voters taken in by the health-care-for-low-income-people-as-“welfare” argument that Reeves, an expansion opponent, regularly uses, is that neighboring Louisiana and Arkansas have both expanded Medicaid. The Arkansas example has some appeal for Mississippi lawmakers. Arkansas officials secured a waiver that allowed federal Medicaid funds to go to private health insurers instead of through state government departments, giving state lawmakers at least the appearance of backing a private plan rather than a government-sponsored one. With nearly half of Mississippi’s rural hospitals at risk for shutting down, Medicaid expansion could relieve some of the burdens of uncompensated care that these hospitals provide to the uninsured.

Owing to its Mountain South heritage, Kentucky has a stronger tradition of two-party competition than the Deep South states.

Yet hovering over that debate is health literacy, a far bigger problem. Heart disease is the state’s number one killer, but health care providers struggle to get people to seek treatments to control hypertension. Improved sex education (Mississippi is an abstinence only/abstinence plus education state) as well as nutrition programs would make a tremendous difference. So would recruiting nurse practitioners and other professionals to provide preventive strategies and fill other gaps in rural areas where doctors are in short supply: When some people finally decide to see a doctor for a disease like diabetes, it may already be too late to save a limb.

In addition to calling for Medicaid expansion, Presley has vowed to get rid of the state’s grocery tax and cut car tag fees. There is a 7 percent sales tax on groceries, the highest in the country. The exorbitant tax levied on vehicles, also among the country’s highest, can run into the hundreds if not thousands of dollars. Reeves prefers cutting or doing away with the income tax to help attract businesses and workers to the state. Business leaders, for their part, have resisted that idea, fearing that the move would create new financial problems.

If any one thing is going to drag Reeves down, it is the scandal that saw about $77 million in Temporary Assistance for Needy Families funds over a four-year period diverted to projects run by associates of Reeves. Those associates included Paul Lacoste, who held a fitness boot camp that Reeves attended, and former NFL quarterback Brett Favre, who secured $5 million in state funding for a University of Southern Mississippi volleyball stadium (USM is Favre’s alma mater and where his daughter had played on the school’s volleyball team). The governor approved the firing of Brad Pigott, the former U.S. attorney appointed to investigate these dealings. Reeves, who often touts his own “numbers guy” skills (his official biography notes that “he holds the Chartered Financial Analyst designation”), was the lieutenant governor overseeing budget deliberations when these diversions occurred. The chief executive has not been directly implicated in the scandals.

Four years ago, Reeves won the governorship by only five percentage points, 52 percent to 47 percent, in a state accustomed to 60-40 Republican romps over Democrats. Today, between his wealth and reputation for cronyism, his bland speeches, the rural hospital care crisis, and the taint, if not the receipts, of a scandal that won’t quit, Reeves has been propelled into the ranks of the country’s most unpopular governors.

Presley’s key priorities could resonate with poor and white working-class voters if he can persuade them that Reeves hasn’t done much to materially improve their economic standing and is a corrupt pol. His biography is compelling: He lost his father as a child and grew up in a family headed by a single mother who faced stretches without electricity or running water and went on to become mayor of Nettleton, his small hometown, and a utilities regulator. Being a second cousin to Elvis (yes, that Elvis) doesn’t hurt, but so far that distinction hasn’t helped his anemic name recognition. An August Mississippi Today/Siena College poll of 650 likely voters found that 35 percent of those surveyed didn’t know enough about him a little more than two months before Election Day.

“There is absolutely a move afoot amongst Black women for Brandon [Presley] because things have been so bad,” says Pamela Shaw, president of P3 Strategies, a Jackson government relations and public affairs firm. And not just among Black women, she adds. “From what I hear across the state in some of my interactions with white women who don’t like Tate, they really don’t like the Dobbs decision; they will vote for Brandon. They are not going to be public about it just because of their churches and their husbands.”

For Presley to get into the governor’s mansion, he’ll have to navigate Interstate 55. The north-south artery, which runs from the Mississippi-Tennessee border down through Jackson (whose water crisis has not factored into the contest) to the Gulf Coast and New Orleans, practically divides the state into its racialized voting halves. White voters are largely east of I-55 and Black voters, in the Mississippi Delta to the west.

Presley also has to do better than Jim Hood, the Democrat Reeves defeated in the 2019 governor’s race, did on the Gulf Coast—Reeves’s own territory—in cities like Gulfport and Biloxi, while pulling in votes from the Mississippi suburbs of Memphis and from his own northeast home base. Like Presley, Hood is from northeast Mississippi, but he lost all of those counties. He also lost DeSoto County, in the Memphis metro area, one of the state’s fastest-growing counties.

LOUISIANA’S DEEP EVANGELICAL AND CATHOLIC ETHOS makes an abortion discussion taboo in rural conservative areas of the state. Politics had divided Catholics in the south and southwest and Protestants in the north until Republicans brought them together around their shared opposition to abortion. In 2006, Louisiana passed a trigger ban that was signed into law by Democratic Gov. Kathleen Blanco. In 2022, the term-limited Edwards updated the law to include fines and prison terms for doctors, and amended it to include specific “medically futile” exceptions for a fetus, such as profound and irredeemable congenital and chromosomal anomalies.

Abortion clinics in New Orleans, Baton Rouge, and Shreveport have all moved out of state. Earlier this year, state lawmakers failed to add rape and incest exceptions to the state’s abortion ban. Like Mississippi, Louisiana is a perennial bottom dweller in measures of poverty and infant and maternal health.

A crabs-in-a-barrel fight is now under way among the Republican contenders to dislodge Jeff Landry, the far-right Republican attorney general, from his so-far secure perch atop the polls before the state’s mid-October open “jungle” primary. The top two finishers will go on to the November general election if no one gets 50 percent of the vote. The issue that gets the most attention from the candidates is crime, which topped an August poll on the key issues facing voters.

The Democrat in the free-for-all, Shawn Wilson, is a first-time candidate who lacks both a statewide profile and the necessary megabucks. As the only Democrat in the open primary, he may well advance to November along with Landry. Since the end of June, they are the only two candidates polling above 20 percent. In the first debate of the campaign season, Wilson supported exceptions for rape and incest, left decision-making on abortion to his wife and daughters, and believes that voters should be able to weigh in on the issue via a ballot initiative.

NO MATTER THE OUTCOME OF THIS FALL’S ELECTIONS, all three of these states now have such severe restrictions on abortion that they could see some physicians, reproductive health care providers, and medical students depart for less restrictive states, particularly if privacy and travel issues come into play. It’s a devastating turn of events that threatens to increase the number of maternal care deserts in these still largely rural states.

In supporting abortion rights, Beshear is taking the greatest chance of any of this year’s gubernatorial candidates in what promises to be a tight contest in a favorable but still challenging climate. In Mississippi, Presley has so far shied away from making an issue of the Republicans’ abortion overreach and their support for government intrusion in people’s lives—a talking point that Republicans like to lob at opponents until they see their own reflections in a mirror. The impenetrable Black/white partisan divide means that a Democrat has to build an almost perfect electoral coalition to prevail against an incumbent governor who’s failing in every single category except a certain shade of whiteness.

The Dobbs decision opened the way for the region to pare back even the limited reproductive decision-making people had before Roe fell. As the South settles into a period of harsh government overreach and creeps toward more privacy restrictions, whatever the outcome of their upcoming gubernatorial contests, these three states likely won’t nudge the rest of the country toward any sort of acceptance of Dobbs and the turmoil it has unleashed.