Although 38 states have legalized Cannabis for medical use, it remains prohibited on the federal level. But what many people don’t realize is that the federal government actually established a legal medical marijuana program of its own over four decades ago — one that’s provided a handful of patients with free weed from Uncle Sam himself.

Reefer for Research

America’s original medical marijuana program began, surprisingly, at the University of Mississippi School of Pharmacology. In 1968, UMSP was awarded the first and only official government contract to supply the National Institute on Mental Health with marijuana so researchers could study its effects. Among the first scientists approved to dip into Uncle Sam’s secret stash were Dr. Robert Hepler and Dr. Ira R. Frank at UCLA. In 1971, the duo published a study in the Journal of the American Medical Association titled “Marihuana Smoking and Intraocular Pressure,” which indicated that THC reduced eye pressure, suggesting Cannabis was a possible treatment for glaucoma and other optical conditions. Unbeknownst to them, a young man across the country would soon arrive at the same conclusion through experimentation of his own.

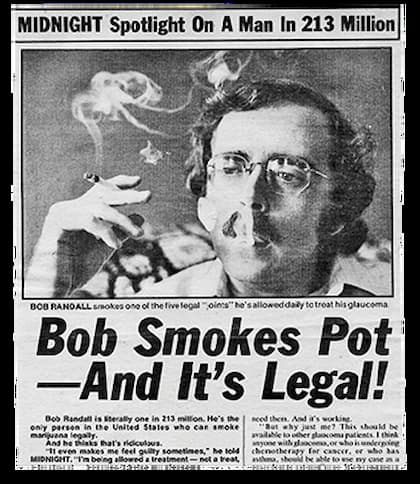

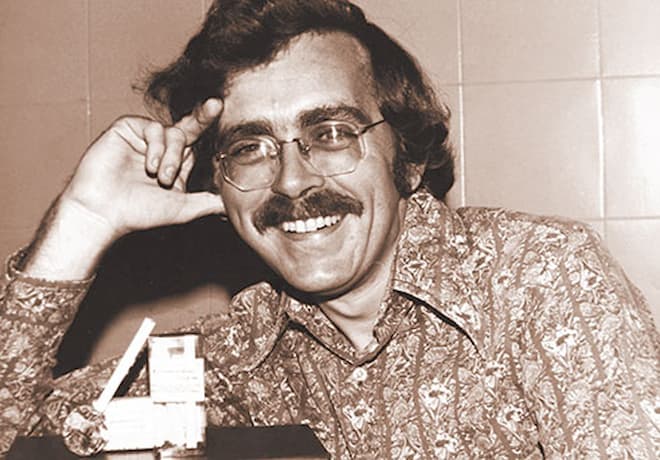

Robert Randall

In 1971, 23-year-old Washington, D.C., taxi driver Robert Randall was diagnosed with glaucoma and told he’d likely be blind within five years. The prescribed eyedrops only seemed to make things worse. Then one day he smoked a joint, and to his surprise, it eased his eye pain and improved his vision. Randall began smoking weed regularly and eventually decided to start growing it himself. Unfortunately, in summer 1975, Randall and his wife Alice returned from vacation to find the four plants on their sun deck gone and a search warrant on their kitchen table, along with a note from the MPD requesting that they turn themselves in. It seems police noticed their plants while raiding a neighboring apartment and visited their place next.

Randall and his wife were arrested and charged with possession. Had they pled guilty, they could’ve simply paid a small fine and moved on… but within a week of their arrest, Randall learned about the Hepler/Frank study and instead decided to fight it — pleading “not guilty” and invoking the rarely-used Common Law Doctrine of Necessity to mount the first-ever medical marijuana defense. He even got Dr. Hepler to testify on his behalf. As a result, on Nov. 24, 1976, the judge ruled in Randall’s favor — dismissing the charges and affirming his use of marijuana as a “medical necessity.” That verdict marked the first time in 40 years that the U.S. government acknowledged that Cannabis may have medicinal use.

Meanwhile, Randall had also filed a petition in May 1976 with the DEA and National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) requesting medical access to that Mississippi marijuana. Within weeks of his historic verdict, NIDA granted that petition, making him the first legally sanctioned medical marijuana user in American history.

But his battle wasn’t over yet: as retaliation for criticizing the agencies in the media, an FDA subcommittee imposed harsh restrictions on where and how often he could obtain his meds, effectively cutting him off. In response, on May 6, 1978, Randall filed a sweeping lawsuit against the FDA, DEA, NIDA, DOJ and Department of Health, Education and Welfare. Apparently, officials were so terrified of the case going to trial that within 48 hours they’d settled out of court. The new agreement allowed Randall to receive Cannabis via a standard written prescription as part of a new FDA research effort called the Compassionate Investigational New Drug program, or IND.

Compassionate IND

Founded as a direct result of the settlement in the Randall v. U.S. case, the IND program was a concession made by NIDA to allow a select few patients with specific conditions to receive a monthly allotment of Cannabis from Ole Miss for “compassionate reasons.” After the plants were harvested and dried, they were shipped in large metal drums to a facility in North Carolina, where they were crushed, sifted and watered, then fed into a bulk cigarette-making machine. Next, those joints were freeze-dried and loaded 300-deep into round steel canisters, which were then stored in a freezer until being shipped off to the pre-approved doctor or pharmacist.

The government attempted to keep this new IND program under wraps because its very existence was a tacit admission that Cannabis did in fact have medicinal value — a direct contradiction to their official position and its classification under Schedule 1 of the Controlled Substances Act. This is why it took nearly four years before another patient would be reluctantly admitted to the program: namely, Irvin Rosenfeld, a financial adviser in Florida.

Irvin Rosenfeld

Since the age of 10, Rosenfeld suffered from a rare disease called Multiple Congenital Cartilaginous Exostoses — a condition that causes painful bone tumors to grow at his joints. Throughout his life, Rosenfeld underwent numerous surgeries and tried various medications before accidentally discovering that smoking marijuana helped relieve his pain and inflammation. Originally against illegal drugs, he was essentially peer pressured into smoking it while attending college in Miami in 1971. It didn’t affect him much at first, but one day, he smoked a joint while playing chess and came to the remarkable realization that he’d been sitting for over 30 minutes with no pain for the first time in years.

The following year, he dropped out of college and moved back to his home state of Virginia, where he and his doctor petitioned the FDA for approval to conduct their own medical study. After being stonewalled for years, Rosenfeld was about to give up hope. Then, in 1977, he met Randall at a college speaking engagement and was encouraged to keep fighting.

“He said, ‘You know, the government has no intentions of ever giving it to anyone else, but if anybody has a chance, you do.’”

With Randall’s guidance, in 1982, the FDA finally held a hearing for his case. After listening to his “very eloquent and convincing” testimony, the FDA granted his request, and in 1983 he became the second person accepted into the IND program.

With the help of Randall and Rosenfeld, more and more patients began petitioning for access to the program, including Iowans Barbara Douglas and George McMahon, Nebraska grandmother Corrine Millet, and Vietnam vet Lynn Pierson. But perhaps the best-known NID participant is the feisty firebrand, Elvy Musikka.

Enter Elvy

Originally from Columbia, Elvy Musikka was born with congenital cataracts. At age 6, she had the first of many surgeries — some of which did more harm than good. In addition to her cataracts, Musikka was also diagnosed with glaucoma in 1975. At that point, her doctor unofficially advised her to use marijuana to try to save her sight. Like Rosenfeld, she had been against drug use up until that point, but in 1976, after learning about Randall’s case, she decided to try some pot brownies. The results were, according to her, “nothing short of a miracle.”

Musikka began using Cannabis regularly, and in 1980, she started growing a half dozen plants in her backyard in Hollywood, Florida. For nearly a decade, she grew and used Cannabis medicinally without legal incident — that is, until 1988, when a boarder she was trying to evict dropped the dime on her. When the police arrived on the evening of March 4, she didn’t try to hide the plants. Instead, she explained that they were her medicine and without them she’d go blind. Nevertheless, they confiscated her weed, arrested her and charged her with cultivation.

Musikka was facing a possible sentence of five years in prison, but rather than calling an attorney, she went straight to the media. Her story quickly caught the attention of both NORML attorney Norm Kent (who offered to represent her pro bono) and Randall, who also offered his assistance. Thanks to testimony by Randall and her ophthalmologist at her trial that August, the judge ruled in her favor, declaring: “I don’t see where a better case could ever be made for medical necessity. In this case, Miss Musikka is trying to preserve herself from serious bodily injury.”

Two months after her acquittal, Musikka was accepted into the IND, becoming the first woman to receive Cannabis through the program.

Blind From the Bunk

Unfortunately, Musikka’s struggles were far from over. After she moved to Eugene, Oregon, in 2005, NIDA refused to ship the tins to her new location, forcing her to fly back to Florida each year to pick up her joints. She also faced ongoing harassment at airports and on the road from law enforcement agents who didn’t understand or care about her unique legal status. But perhaps the greatest injustice inflicted on Musikka — and, in fact, all of the IND patients — was the poor quality Cannabis they received. Not only was U-Miss’s weed loaded with seeds and stems, freeze-dried, and often many years old, but its potency was also abysmal — containing just 2% to 6% THC and practically zero other cannabinoids. Tragically, it was one particularly bad batch in 2012 that indirectly caused Musikka to go completely blind in her right eye.

“They sent us a bunch of garbage with no THC. It was hemp — which I love to wear, but it didn’t do anything for my glaucoma,” she told Freedom Leaf.

Apparently, the lack of THC (which she assumed she was getting from the joints) caused the pressure in her eyes to hit “critical levels.” In turn, this led doctors to perform emergency surgery, which they botched — causing the detachment of her retina and the loss of her optic nerve.

End of an Era

At its peak in 1991, 43 people had been approved for the IND, but only 15 of them ever actually received any meds from the feds. Reportedly, government officials grew nervous about the program getting out of hand due to a large influx of applications from AIDS patients during the late ’80s. And so, in 1992, the Bush administration directed NIDA to stop accepting new patients, effectively ending the program for anyone who wasn’t grandfathered in — including nearly 300 patients awaiting approval.

“The government was never comfortable with this program,” Rick Doblin, executive director of MAPS, told the LA Times in 2015. “They are just waiting for all the people in it to die.”

Sadly, that’s gradually what happened. Today, only Rosenfeld and Musikka remain. Though still technically enrolled in the program, Musikka opted to stop receiving joints in 2020 — partly because she tired of flying to Florida, and partly because she’d rather smoke better bud. Which, of course, leaves Rosenfeld as the last patient still smoking Uncle Sam’s schwag.

“I appreciate what the government has done and hope it never stops,” he once said. “I feel very, very fortunate … I shouldn’t have been alive and I’m still alive. I take no other medicines; I’m in great shape because of the Cannabis. I’m living proof that medical Cannabis is real medicine.”